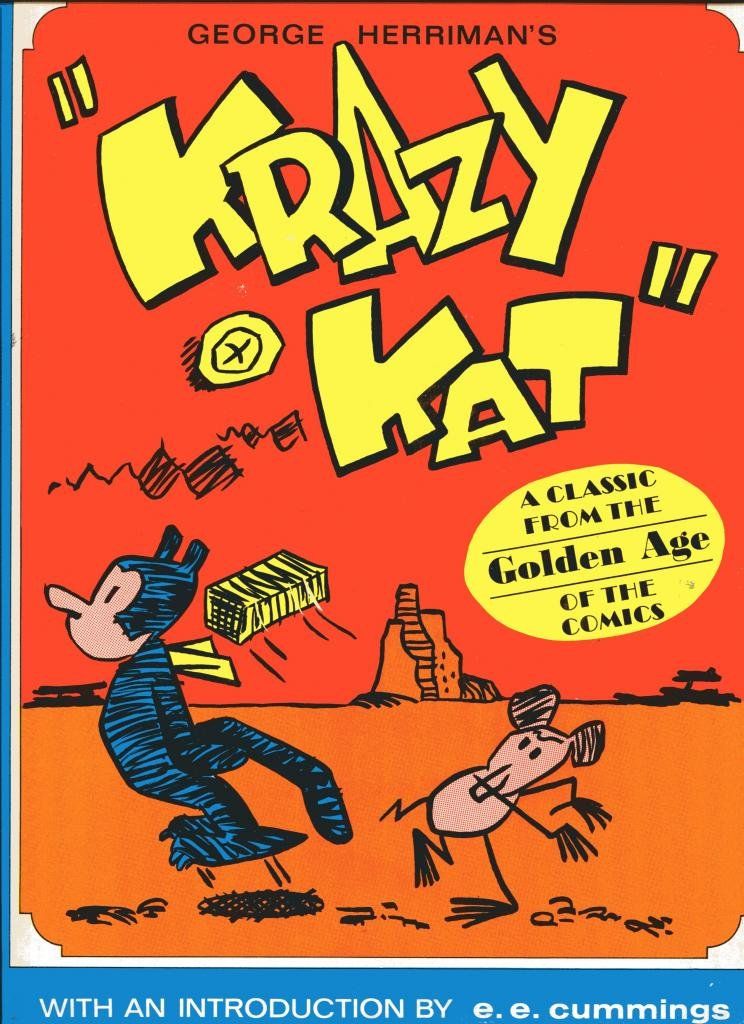

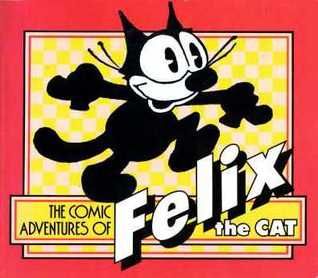

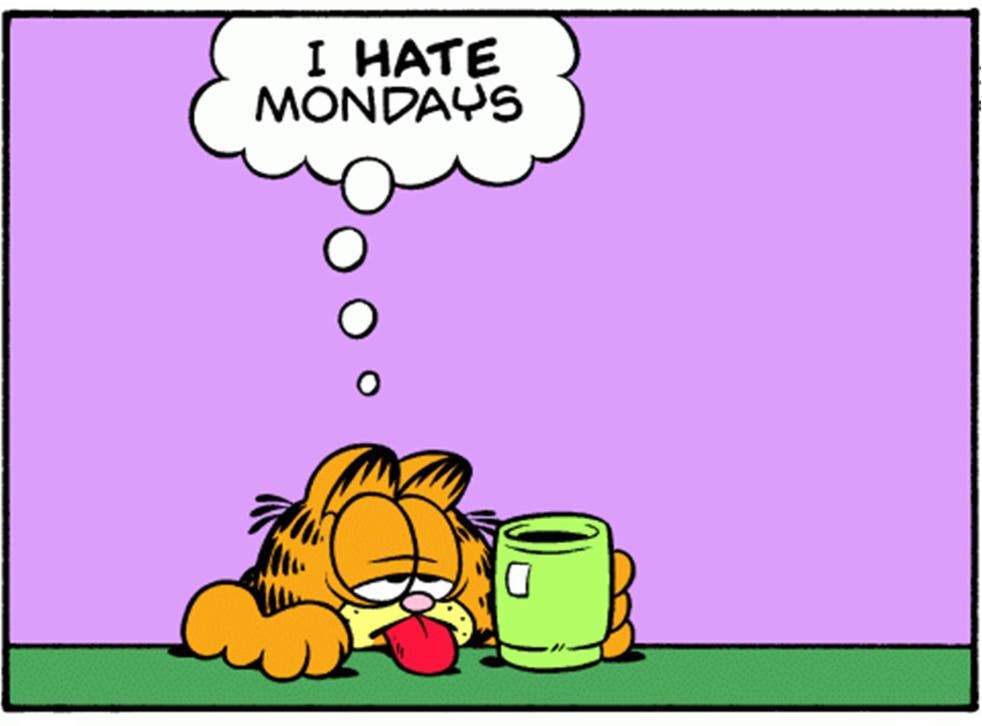

Comic strips as we commonly know them first began appearing in North American newspapers in the 19th century, and were still most often used for political satire. The first feline to graze the funny pages in North America was Krazy Kat, created by George Herriman, which first appeared in the New York Evening Journal in 1913. The comic followed the misadventures of a simple-minded and carefree cat named Krazy and a short-tempered, neurotic mouse named Ignatz. Krazy develops an unconventional love for Ignatz which he does not reciprocate, scheming constantly to throw bricks at Krazy’s head, which Krazy interprets as a sign of love. An obvious early influence and inspiration for the cartoons of Hanna-Barbera and Looney Tunes that would appear later in the 20th century, Krazy Kat was the first “frivolous” comic strip to be praised as legitimate art by critics, despite only achieving moderate popularity in newspaper syndication. In 1924, renowned art and culture critic Gilbert Seldes wrote an extensive panegyric dedicated to Krazy Kat, which he deemed “the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.” Krazy Kat ceased publication in June 1944. Another famous feline known as Felix the Cat was on his way to fame in fortune in the 1920s. First appearing in silent shorts around 1919, Felix achieved large popularity as a comic strip on the page starting in 1923, capitalizing on his success as one of the most recognizable cartoon cats in film history and popular culture. According to the now-defunct website Golden Age Cartoons, Felix “rocketed to fame, holding a spot as the world’s most popular cartoon character until the advent of Mickey Mouse … When Felix’s screen career faded in the 1930s, the cat spent a few decades in a memorable series of comic books and strips.” With the arrival of sound cartoons soon popularized by Walt Disney, Felix the Cat slipped from prominence as his creators Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer were allegedly unwilling to have Felix make the jump from silent to sound. Operations ended in 1932 before Felix saw a brief resurrection with The Van Beuren Corporation in 1936. Messmer continued to draw the nationally syndicated Felix the Cat comic strips himself until 1943, when he began publishing monthly Felix comic books for Dell Comics. The Felix comic strip was ghostwritten by Jack Mendelsohn for a time until Messmer retired in 1954, handing the comic strip operation over to his assistant Joe Oriolo — creator of Casper the Friendly Ghost — who concluded Felix the Cat in 1966. Felix did, however, enjoy a second brief resurgence in the 1980s when he began appearing in the short-lived comic strip Betty Boop and Felix. The popularity of the Krazy and Felix comic strips in North American newspapers during the first half of the 20th century was enough to signify to publishers and advertisers alike that there was something unique to anthropomorphized cats and their ability to both comfort and entertain readers with their fast wit and keen observations that were often at the forefront of American culture. Sylvester the Cat, the beloved Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies character who had first appeared in animated shorts in 1939, would soon also make the jump to the page in 1952 with Tweety and Sylvester, a comic initially published by Dell Comics in their Four Color anthology series. The characters proved so popular in comic form that Dell would make Tweety and Sylvester its own comic book, which ran until 1962 and again with Gold Key Comics until 1972. But the famed cat and bird duo would make their final appearance to date in comics with the DC crossover Catwoman/Tweety and Sylvester, which ran for one issue in August 2018. Similarly, the success that Hanna-Barbera enjoyed with their Tom and Jerry animated shorts in the 1940s led to a syndicated comic strip between 1950 and 1952 and again from 1989 to 1994. But no cat comic would compare to the cultural impact of a certain orange fellow whose sarcastic quips and relentless laziness would make him a fast and bonafide phenomenon. Garfield, created by Jim Davis and first appearing in 1976, follows the namesake cat as he faces his hatred of Mondays and love of lasagna. It co-stars his owner Jon, their dog Odie, and Garfield’s beloved teddy bear Pookie. Unlike the aforementioned cartoon cats who first found recognition on the screen before moving to the page, Garfield’s popularity simulated an effect of the opposite wherein the success of the comic strip led to a list of television specials (where the character was memorably voiced by Lorenzo Music) and two computer-animated feature films in the 2000s, Garfield: The Movie and Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties. Predating the internet and social media by several decades, Garfield maintains his popularity into the 2020s with his signature brand of bitter and lazy, which somehow remains impeccably on-brand in the Twitter and Instagram age. According to Brian Boone from Grunge, “Garfield is a cultural institution at this point, enjoying a level of fame for a comic strip character previously bestowed only on the likes of Charlie Brown or Snoopy. He’s been part of the world for so long, and in such a steady, easily understandable form, that he even gets under people’s skin.” Garfield was, however, preceded by another famous feline: Heathcliff. Created by George Gately and first appearing in 1973, Heathcliff quickly became known for his ability to harass dogs and haunt local fish markets. Named after the character in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff — much like Garfield — also leaped from the page to the screen in two television series in the 1980s where he was voiced by Mel Blanc of Looney Tunes fame, becoming one of the last original characters Blanc would perform until his death in 1989. Heathcliff: The Movie appeared in 1986 and a computer-animated feature film was set for release with a trailer appearing around 2010, with nothing further to materialize. Despite their similarities and competitions for success, the Garfield vs. Heathcliff debate was quickly settled in October 1981 by New Jersey’s Ashbury Park Press, who asked readers to decide which cat should be their leading comic strip. Garfield won, but not by much: he drew 326 votes while Heathcliff received 324. One reader was not pleased with either choice and famously wrote to the paper, “Bring us Marmaduke.” Some of my fondest childhood memories are of my grandmother, my treasured Nanny, saving pages and pages of comics for me from our local newspaper. Spending several weekday afternoons at her house, it just wasn’t the same when my dad started subscribing to the newspaper, thus allowing me to read the comics from home. There was always something special about reading the funny pages, many of whom always contained a cat or two, from her house. Even now, as the owner of several Garfield anthologies I lovingly poured over as a kid that are now packed away somewhere, it’s still easy to pull one out and flip through the colorfully funny pages, recalling a time when the quick wit of a comic could unite a culture in one strip. Until we learn to do that again, may we take a page from Garfield’s book and continue hating Mondays, avoiding exercise, and eating a whole lasagna if we feel like it.