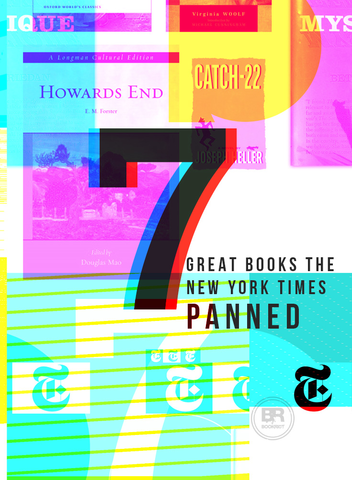

Of particular interest are the things the review got wrong. Commendably, the editors of Books of the Century not only chose to include critical missteps, but they even highlighted them (calling them “Oops!” entries). Here are a few highlights

On Henry James’ The Golden Bowl: It seems to me to present Mr. James at his worst…We find, standing for subtlety, a kind of restless finicking inquisitiveness, a flutter of aimless conjecture, such as might fall to a village spinster in a department store. Mr. James, the prolix, the incoherent, the indecisive; it is of this Mr. James that we carry an impression from The Golden Bowl. Thoughts: Aside from the shift from the first-person singular to the first-person plural, the notable feature here is that the reviewer seems to mistake James’ interest with that of the characters in The Golden Bowl. To my mind, the “aimless conjecture” and “indecisive” descriptors are aptly applied to the characters rather than James himself. Forgetting that the author’s concerns and interests do not necessarily align with the concerns and interests of the characters is a common reviewing mistake–and rather refreshing to see from the Grey Lady.

On E.M. Forster’s Howards End: As a social philosopher, evidently, Mr. Edward M. Forster has not arrived at very positive convictions. He evinces neither power nor inclination to come to grips with any vital human problem. Thoughts: Ah, the good old days when one could chastise a writer for not “coming to grips with any vital human problem” unironically (and use clichés like “come to grips” with impunity). Those who love Forster love him in part, I think, for his lack of moral certainty or judgment. That this reviewer expected an identifiable “social philosophy” tells us much about the moment: just seven years later, criticism in this vein would be seen as woefully naive.

On Virginia Woolf’s The Voyage Out: This English novel, by an English writer, gives promise in its opening chapters of much entertainment. Later, the reader is disappointed. That the author knows her London in its most interesting aspects there can be no doubt. But aside from a certain cleverness–which, being all in one key, palls on one after going through a hundred pages of it–there is little in this offering to make it stand out from the ruck fo mediocre novels which make far less literary pretension. Thoughts: You can be smug. You can be condescending. And you can even be wrong. But you can’t be all three at once. Or so I thought.

On J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye: This Salinger, he’s a short story guy. And he knows how to write about kids. This book though, it’s too long. Gets kind of monotonous. And he should’ve cut out a lot about these jerks and all that crumby school. They depress me. Thoughts: It has yet to be shown that satirical impersonation is a viable mode of literary criticism. Usually, the writer comes off as an ironical jackass; this case is no exception. Still, there is a whisper of truth about Salinger’s gift for the short-story, not as a mark against Catcher, but as a foreshadowing of his long publishing drought as he struggled to contain his opus about The Glass family. The unruliness of the novel form itself seemed to be a part of the problem, and this reviewer presciently suggested he stick to the short story.

On Joseph Heller’s Catch-22: Catch-22 has much passion, comic and fervent, but it gasps for want of craft and sensibility. If Catch-22 were intended as a commentary novel, such sideswiping of character and action might be taken care of by thematic control. It fails here because half its incidents are farcical and fantastic. Thoughts: First, I’m not sure you can “gasp for want.” Second, slamming Catch-22 for “craft and sensibility” is a little like panning a Ferrari because there’s not much trunk space: it is just completely and utterly beside the damn point. Third, how delicious that a book criticized for lack of thematic control would itself be a symbol for all the contradictions of late 20th American life. What’s that phrase for either way you’re wrong?

On Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique: Sweeping generalities, in which this book necessarily abounds, may hold a certain amount of truth but often obscure the deeper issues. It is superficial to blame the “culture” and its handmaidens, the women’s magazines, as she does. What is to stop a woman who is interested in national and international affairs from reading magazines that deal with those subjects? Thoughts: These would be only moderately obtuse points coming from a freshman. Coming from a NY Times reviewer, they are embarrassing. Also, what is more “superficial” than a leading, block-headed question that sounds like an obvious truth but actually demonstrates the problem?

On Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange: With his tongue popping in and out of his cheek, Mr. Burgess satirizes both the sociological and the penal approach to juvenile crime, literary proletarianism, and anything else in his path. Written in a pseudo-criminal cant, A Clockwork Orange is an interesting tour-de-force, though not up to the level of the author’s previous two novels. Thoughts: Besides not quite liking Clockwork enough, this seems pretty right to me, though the “interesting tour-de-force” is a frustrated phrase. I suspect that satires are particularly easy for a critic to get wrong, since much of what a good satire accomplishes is only apparent in hindsight.